[ad_1]

BBC/Kostas Kallergis

BBC/Kostas KallergisUnder heavy gray skies and a skinny coating of snow, hulking gray and inexperienced Cold War relics recall Ukraine’s Soviet previous.

Missiles, launchers and transporters stand as monuments to an period when Ukraine performed a key function within the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons programme – its final line of defence.

Under the partially raised concrete and metal lid of a silo, an enormous intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) peeks out.

But the missile is a reproduction, cracked and mouldy. For virtually 30 years, the silo has been stuffed with rubble.

The entire sprawling base, close to the central Ukrainian metropolis of Pervomais’ok, has lengthy since was a museum.

As a newly unbiased Ukraine emerged from below Moscow’s shadow within the early Nineteen Nineties, Kyiv turned its again on nuclear weapons.

But practically three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion, and with no clear settlement amongst allies on find out how to assure Ukraine’s safety when the struggle ends, many now really feel that was a mistake.

Thirty years in the past, on 5 December 1994, at a ceremony in Budapest, Ukraine joined Belarus and Kazakhstan in giving up their nuclear arsenals in return for safety ensures from the United States, the UK, France, China and Russia.

Strictly talking, the missiles belonged to the Soviet Union, to not its newly unbiased former republics.

But a 3rd of the USSR’s nuclear stockpile was situated on Ukrainian soil, and handing over the weapons was a considered a major second, worthy of worldwide recognition.

“The pledges on security assurances that [we] have given these three nations…underscore our commitment to the independence, the sovereignty and the territorial integrity of these states,” then US President Bill Clinton stated in Budapest.

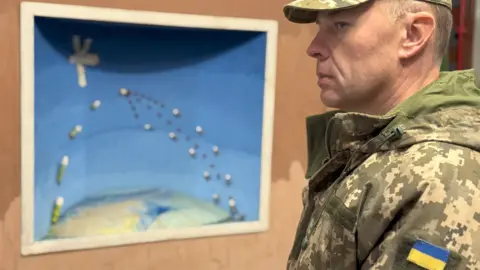

As a younger graduate of a navy academy in Kharkiv, Oleksandr Sushchenko arrived at Pervomais’ok two years later, simply as the method of decommissioning was getting below method.

He watched because the missiles have been taken away and the silos blown up.

Now he’s again on the base as one of many museum’s curators.

BBC/Kostas Kallergis

BBC/Kostas KallergisLooking again after a decade of distress inflicted by Russia, which the worldwide group has appeared unable or unwilling to forestall, he attracts an inevitable conclusion.

“Seeing what’s happening now in Ukraine, my personal view is that it was a mistake to completely destroy all the nuclear weapons,” he says.

“But it was a political issue. The top leadership made the decision and we just carried out the orders.”

At the time, all of it appeared to make excellent sense. No-one thought Russia would assault Ukraine inside 20 years.

“We were naive, but also we trusted,” says Serhiy Komisarenko, who was serving as Ukraine’s ambassador to London in 1994.

“When Britain and United States and then France joined,” he says, “we were thinking that’s enough, you know. And Russia as well.”

For a poor nation, simply rising from a long time of Soviet rule, the concept of sustaining a ruinously costly nuclear arsenal made little sense.

“Why use money to make nuclear weapons or keep them,” Komisarenko says, “if you can use it for industry, for prosperity?”

But the anniversary of the fateful 1994 settlement is now being utilized by Ukraine to make some extent.

Appearing on the Nato international ministers’ assembly in Brussels this week, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Andriy Sybiha brandished a inexperienced folder containing a replica of the Budapest Memorandum.

“This document failed to secure Ukrainian and transatlantic security,” he stated. “We must avoid repeating such mistakes.”

A press release from his ministry referred to as the Memorandum “a monument to short-sightedness in strategic security decision-making”.

The query now, for Ukraine and its allies, is to search out another option to assure the nation’s safety.

For President Volodymyr Zelensky, the reply has lengthy been apparent.

“The best security guarantees for us are [with] Nato,” he repeated on Sunday.

“For us, Nato and the EU are non-negotiable.”

Despite Zelensky’s often passionate insistence that solely membership of the Western alliance can guarantee Ukraine’s survival towards its giant, rapacious neighbour, it’s clear Nato members stay divided on the problem.

In the face of objections from a number of members, the alliance has to this point solely stated that Ukraine’s path to eventual membership is “irreversible”, with out setting a timetable.

In the meantime, all of the speak amongst Ukraine’s allies is of “peace through strength”. to make sure that Ukraine is within the strongest potential place forward of potential peace negotiations, overseen by Donald Trump, a while subsequent yr.

“The stronger our military support to Ukraine is now, the stronger their hand will be at the negotiating table,” Nato Secretary General Mark Rutte stated on Tuesday.

Unsure what Donald Trump’s strategy to Ukraine shall be, key suppliers of navy help, together with the US and Germany, are sending giant new shipments of kit to Ukraine earlier than he takes workplace.

Reuters

ReutersLooking additional forward, some in Ukraine are suggesting {that a} nation severe about defending itself can’t rule out a return to nuclear weapons, significantly when its most necessary ally, the United States, could show unreliable within the close to future.

Last month, officers denied reviews {that a} paper circulating within the Ministry of Defence had urged a easy nuclear gadget could possibly be developed in a matter of months.

It’s clearly not on the agenda now, however Alina Frolova, a former deputy defence minister, says the leak could not have been unintentional.

“That’s obviously an option which is in discussion in Ukraine, among experts,” she says.

“In case we see that we have no support and we are losing this war and we need to protect our people… I believe it could be an option.”

It’s laborious to see nuclear weapons returning any time quickly to the snowy wastes exterior Pervomais’ok.

Just one of many base’s 30m-deep command silos stays intact, preserved a lot because it was when it was accomplished in 1979.

It’s a closely fortified construction, constructed to resist a nuclear assault, with heavy metal doorways and subterranean tunnels connecting it to the remainder of the bottom.

In a tiny, cramped management room on the backside, accessible by an much more cramped elevate, coded orders to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles would have been acquired, deciphered and acted upon.

Former missile technician Oleksandr Sushchenko exhibits how two operators would have turned the important thing and pressed the button (gray, not crimson), earlier than taking part in a Hollywood-style video simulation of a large, international nuclear trade.

It’s faintly comedian, but additionally deeply sobering.

Getting rid of the biggest ICBMs, Oleksandr says, clearly made sense. In the mid-Nineteen Nineties, America was not the enemy.

But Ukraine’s nuclear arsenal included a wide range of tactical weapons, with ranges between 100 and 1,000km.

“As it turned out, the enemy was much closer,” Oleksandr says.

“We could have kept a few dozen tactical warheads. That would have guaranteed security for our country.”

[ad_2]

Source link