[ad_1]

AFP

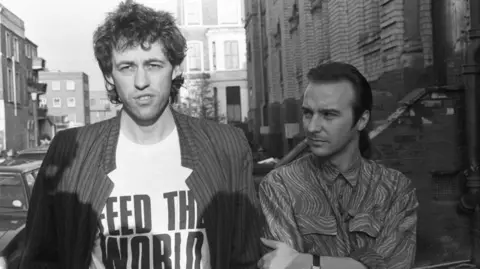

AFPForty years on from the unique recording, the cream of British and Irish pop music previous and current are as soon as once more asking whether or not Ethiopians know it’s Christmas.

In 1984, responding to horrific photos of the famine in northern Ethiopia broadcast on the BBC, musicians Bob Geldof and Midge Ure corralled a number of the largest stars of the period to document a charity music.

The launch of the Band Aid single, and the Live Aid live performance that adopted eight months later, grew to become seminal moments in movie star fundraising and set a template that many others adopted.

Do They Know It’s Christmas? is again on Monday with a recent mixture of the 4 variations of the music which were issued over time.

But the refrain of disapproval in regards to the monitor, its stereotypical illustration of a whole continent – describing it as a spot “where nothing ever grows; no rain nor rivers flow” – and the best way that recipients of the help have been considered as emaciated, helpless figures, has grow to be louder over time.

“To say: ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’ is funny, it is insulting,” says Dawit Giorgis, who in 1984 was the Ethiopian official answerable for getting the message out about what was taking place in his nation.

His incredulity a long time on is apparent in his voice and he remembers how he and his colleagues responded to the music.

“It was so untrue and so distorted. Ethiopia was a Christian country before England… we knew Christmas before your ancestors,” he tells the BBC.

But Mr Dawit has little question that the philanthropic response to the BBC movie, by British journalist Michael Buerk and Kenyan cameraman Mohamed Amin, saved lives.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the top of Ethiopia’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission he had managed to smuggle the TV crew into the nation. This was regardless of the federal government at the moment, which was marking 10 years of Marxist rule and combating a civil struggle, not wanting information of the famine to get out.

“The way the British people responded so generously strengthened my faith in humanity,” he says, talking from Namibia the place he now works.

He praises the “young and passionate people” behind Band Aid – describing them as “amazing”.

His questioning of the music, while additionally recognising its influence, sums up the controversy for a lot of who would possibly really feel that when lives have to be saved the ends justify the means.

Geldof was usually sturdy in defending it responding to a recent article in The Conversation in regards to the “problematic Christmas hit”.

“It’s a pop song [expletive]… The same argument has been made many times over the years and elicits the same wearisome response,” he’s quoted as saying.

“This little pop song has kept hundreds of thousands if not millions of people alive.”

He additionally recognises that Ethiopians have fun Christmas however says that in 1984 “ceremonies were abandoned”.

In an electronic mail to the BBC, Joe Cannon, the chief monetary officer of the Band Aid Trust, stated that previously seven months the charity has given greater than £3m ($3.8m) serving to as many as 350,000 folks by way of a number of initiatives in Ethiopia, in addition to Sudan, Somaliland and Chad.

He provides that Band Aid’s swift motion as a “first responder” encourages others to donate the place funds are missing, particularly in northern Ethiopia, which is as soon as once more rising from a civil struggle.

But this isn’t sufficient to dampen the disquiet.

In the final week, Ed Sheeran has said he is not happy about his voice from the 2014 recording – made to lift funds for the West African Ebola disaster – getting used as his “understanding of the narrative associated with this has changed”.

He was influenced by British-Ghanaian rapper Fuse ODG, who himself had refused to participate a decade in the past.

“The world has changed but Band Aid hasn’t,” he advised the BBC’s Focus on Africa podcast this week.

“It’s saying there’s no peace and joy in Africa this Christmas. It’s still saying there’s death in every tear,” he stated referring to the lyrics of the 2014 model.

“I go to Ghana every Christmas… every December so we know there’s peace and joy in Africa this Christmas, we know there isn’t death in every tear.”

Fuse ODG doesn’t deny that there are issues to be resolved however “Band Aid takes one issue from one country and paints the whole continent with it”.

The manner that Africans had been portrayed on this and different fundraising efforts had had a direct impact on him, he stated.

When rising up “it was not cool to be African in the UK… [because of] the way that I looked, people were making fun of me”, the singer stated.

Research into the influence of charity fundraisers by British-Nigerian King’s College lecturer Edward Ademolu backs this up.

He himself remembers the quick movies shot in Africa by Comic Relief, which had been influenced by Band Aid, and that his “African peers at [a British] primary school would passionately deny their African roots, calling all Africans – with great certainty – smelly, unintelligent and equated them to wild animals”.

Images of dangerously skinny Africans grew to become frequent forex in efforts to elicit funds.

The cowl for the unique Band Aid single, designed by pop artist Sir Peter Blake, options vibrant Christmas scenes contrasted with two gaunt Ethiopian youngsters, in black and white, every consuming what seems to be like a life-saving biscuit.

For a part of the poster for the Live Aid live performance the next 12 months, Sir Peter used {a photograph} of the again of an nameless, bare, skeletal baby.

That picture was used once more within the artwork work for the 2004 launch and it has appeared as soon as extra this 12 months.

For many working within the assist sector, in addition to teachers who research it, there’s shock and shock that the music and its imagery hold coming again.

The umbrella physique Bond, which works with greater than 300 charities together with Christian Aid, Save the Children and Oxfam, has been very vital of the discharge of the brand new combine.

“Initiatives like Band Aid 40 perpetuate outdated narratives, reinforce racism and colonial attitudes that strip people of their dignity and agency,” Lena Bheeroo, Bond’s head of anti-racism and equity, said in a statement.

Geldof had beforehand dismissed the concept Band Aid’s work was counting on “colonial tropes”.

The manner that charities increase funds has undergone huge modifications lately.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile remaining vital, Kenyan satirist and author Patrick Gathara, who typically mocks Western views of Africa, agrees issues have shifted.

“There has been a push within humanitarian agencies to start seeing people in a crisis first as human beings and not as victims, and I think that’s a big, big change,” he tells the BBC.

“In the days of Live Aid, all you really had were these images of starvation and suffering… the idea that these are people were incapable of doing anything for themselves and that was always a misconception.”

The fallout from the Black Lives Matter protests added impetus to the change that was already taking place.

A decade in the past, a Norwegian organisation Radi-Aid made it its mission to focus on the best way that Africa and Africans had been introduced in fundraising campaigns utilizing humour.

For instance, it co-ordinated a mock marketing campaign to get Africans to ship radiators to Norwegians who had been supposedly struggling within the chilly.

In 2017, Sheeran himself won one of their “Rusty Radiator” awards for a movie he made for Comic Relief in Liberia through which he provided to pay for some homeless Liberian youngsters to be put up in a resort room.

The organisers of the awards stated “the video should be less about Ed shouldering the burden alone but rather appealing to the wider world to step in”.

University of East Anglia educational David Girling, who as soon as wrote a report for Radi-Aid, argues that its work is without doubt one of the causes that issues have shifted.

More and extra charities are introducing moral tips for his or her campaigns, he says.

“People have woken up to the damage that can be caused,” he tells the BBC.

Prof Girling’s personal analysis, carried out in Kibera, a slum space in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, confirmed that campaigns involving and centred on those that are the targets of the charitable help might be more practical than the standard prime down efforts.

Many charities are nonetheless below strain to make use of celebrities to assist increase consciousness and cash. The professor says that some media retailers won’t contact a fundraising story until a celeb is concerned.

But work by his colleague Martin Scott means that huge stars can typically distract from the central message of a marketing campaign. Whereas the movie star would possibly profit, the charity and the understanding of the difficulty that it’s engaged on lose out.

If a Band Aid-type mission had been to get off the bottom now it must be centred on African artists, music journalist Christine Ochefu tells the BBC.

“The landscape for African artists and African music has changed so much that if there was a new release it would need to come from afrobeats artists or amapiano artists or afro-pop artists,” she argues

“I don’t think people could get way without thinking about the sentiment and imagery associated with the project and it couldn’t continue the saviour narrative that Band Aid had.”

As King’s College educational Dr Ademolu argues: “Perhaps it’s time to abandon the broken record and start anew – a fresh tune where Africa isn’t just a subject, but a co-author, harmonising its own story.”

You may be taken with:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC[ad_2]

Source link